In December I was invited to present “Letting the Data Tell the Story About Women Coaches” at the first-ever BREAKTHROUGH SUMMIT FOR WOMEN IN SPORT, hosted in WeCOACH and Hudl.

In December I was invited to present “Letting the Data Tell the Story About Women Coaches” at the first-ever BREAKTHROUGH SUMMIT FOR WOMEN IN SPORT, hosted in WeCOACH and Hudl.

See my talk and all the other speakers here.

Nicole M. LaVoi, Ph.D.

In December I was invited to present “Letting the Data Tell the Story About Women Coaches” at the first-ever BREAKTHROUGH SUMMIT FOR WOMEN IN SPORT, hosted in WeCOACH and Hudl.

In December I was invited to present “Letting the Data Tell the Story About Women Coaches” at the first-ever BREAKTHROUGH SUMMIT FOR WOMEN IN SPORT, hosted in WeCOACH and Hudl.

See my talk and all the other speakers here.

While girls and women participation in sports since Title IX has exploded, only about 40% of them are coached by women. The film explores supporting research, dispels false narratives, celebrates female coaching pioneers at all levels of competition and highlights stories of success and hardship. Their stories are the universal stories of women coaches who fight many battles to pursue their passion to coach. Produced in collaboration between Twin Cities Public Television and the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport.

While girls and women participation in sports since Title IX has exploded, only about 40% of them are coached by women. The film explores supporting research, dispels false narratives, celebrates female coaching pioneers at all levels of competition and highlights stories of success and hardship. Their stories are the universal stories of women coaches who fight many battles to pursue their passion to coach. Produced in collaboration between Twin Cities Public Television and the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport.

This week the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport released a new report : 2018 Tucker Center Research Report, Developing Physically Active Girls: A Multidisciplinary Evidence-based Approach.

The report includes eleven chapters written by leading multidisciplinary scholars. Evidence-based chapters include psychological, sociological, and physiological dimensions of girls’ physical activity participation, as well as chapters on sports medicine and the influence of mass media of girls’ health and well-being. Because “girls” are not a singular monolithic group, chapters focus on girls’ intersectional identities and include invisible, erased, and underserved populations such as immigrant girls, girls of color, girls who identify as lesbian, transgender and queer/questioning, and girls with cognitive and physical impairments. The report ends with a Best Practices chapter and a Positive Model for Developing Physically Active Girls to guide thought, program development, interventions and research.

The report includes eleven chapters written by leading multidisciplinary scholars. Evidence-based chapters include psychological, sociological, and physiological dimensions of girls’ physical activity participation, as well as chapters on sports medicine and the influence of mass media of girls’ health and well-being. Because “girls” are not a singular monolithic group, chapters focus on girls’ intersectional identities and include invisible, erased, and underserved populations such as immigrant girls, girls of color, girls who identify as lesbian, transgender and queer/questioning, and girls with cognitive and physical impairments. The report ends with a Best Practices chapter and a Positive Model for Developing Physically Active Girls to guide thought, program development, interventions and research.

To read and download the full report, Executive Summary or the Positive Model click here.

The second piece I wrote for swimswam.com about the false narratives and barriers facing women coaches can be found here.

The second piece I wrote for swimswam.com about the false narratives and barriers facing women coaches can be found here.

In the piece I write, “The lack of women coaches is not the problem, it is a reflection of a problem. That problem is a culture that does not value and support women.”

The first piece outlined 8 Reasons Why Women Coaches Matter. If you think women coaches don’t face barriers, please read the comments on this blog and the piece that started it all, which was about data on lack of women head swimming and diving coaches at the collegiate level.

I recently wrote a guest blog for swimswam.com

As you may or may not know, swimming & diving has very few women coaches and gets on F on our Women in College Coaching Report Card.

You can read my blog titled “8 Reasons Why Women Coaches Matter” here.

In my research I have interviewed Athletic Directors (ADs) on their best practices in recruiting, hiring and retaining women coaches. [to read the full report, click here.] Nearly all of them stated they want to hire “the best” for an open position. The best person, the best fit, the best qualified, the best (i.e., a winner, successful, track record of success), the best of the best! ADs are competitive people, and rightly so! “The best” is part of their everyday language, and not being the best means your job may be on the line.

However, what is not readily apparent in “the best” narrative is the underlying gender bias and gender stereotypes that affect how leadership is valued, perceived, and evaluated.

However, what is not readily apparent in “the best” narrative is the underlying gender bias and gender stereotypes that affect how leadership is valued, perceived, and evaluated.Stereotypes and gender bias are inherent in constructing and reinforcing what a real leader ‘looks like’ and ‘does.’ For example, what it means and has meant historically “to coach”—being assertive and in control, aggressive, ambitious, confident, competitive, powerful, dominant, forceful, self-reliant and individualistic—are characteristics typically associated with men and masculinity. This identity of the ideal/best coach is reinforced by society and the media, where coaches are constructed and held up as heroes and the male coach is a symbol and ultimate expression of the idealized form of masculine character.

Therefore when ADs state they want “the best” coach, this statement automatically privileges and favors male coaches over women, whether intended or not. However, “the best” might also be a coded way ADs can talk about hiring women without

putting themselves or the institution at risk for gender-based discrimination litigation by male applicants.

Clearly, a complex set of conscious and unconscious inferences are contained within persistent and common “hire the best” narratives among college Athletics Directors. The pervasive “best” narrative illuminates the need for bias training and awareness that bias has a potential impact on the perception, recruitment, evaluation and hiring (and firing) of women coaches.

Happy International Women’s Day 2018!

This is the fifth part of my Changing the Narrative for Women Sport Coaches blog series.

You can read I, II, III and IV.

This one will be brief! I often hear that “women don’t want to move their families” as a reason why there are fewer female head coaches. To my knowledge, and I will stand corrected, there is NO empirical data to support this assumption.

This one will be brief! I often hear that “women don’t want to move their families” as a reason why there are fewer female head coaches. To my knowledge, and I will stand corrected, there is NO empirical data to support this assumption.

Are women less likely to move their families than men? Maybe. Maybe Not.

This is why it matters. When this narrative is repeated over and over, it becomes truth and then in turn it begins to affect how women are evaluated, perceived and interacted with in the recruiting and hiring process.

There are many questions, and very little data about this particular narrative. While data is collected, I hope that it will be put to rest until it is proven or refuted.

This marks the fourth blog in the Changing the Narrative about Women Sport Coaches series. Brief review: In Part I and II of this series I laid out how women coaches are framed shapes the discussion, and the numerous “blame the women” narratives that exist. In Part III the “Women don’t apply” narrative was addressed. In this blog I will provide a counter to another common narrative: “Women aren’t as interested in coaching as men.”

Similar to the “women don’t apply” narrative, when fewer women (compared to men) apply for an open position, the fewer number of women provides proof that women aren’t as, or are less, interested in coaching than men. Here is another way to look at this narrative.

?????

In Part I and II of this series, Changing the Narrative for Women Sport Coaches, I laid out how women coaches are framed shapes the discussion, and the numerous “blame the women” narratives that exist. In this blog I will tackle one particular narrative, provide counter narratives and suggest strategies for change.

BLAME THE WOMAN NARRATIVE: Women don’t apply.

BLAME THE WOMAN NARRATIVE: Women don’t apply.

I hear from coaching directors and athletic directors (ADs) they want to hire women, but women just don’t apply. For example, if a head coach job is open an AD might get 45 male and three female applicants. The lack of women applicants provides proof that women don’t apply [subtext: Women CHOOSE not to apply].

Let me provide a few counter narratives and perspectives.

So what is the solution?

Change must occur at ALL LEVELS but it starts with the AD because that person has the most power in the system!

Strategies for the AD to consider:

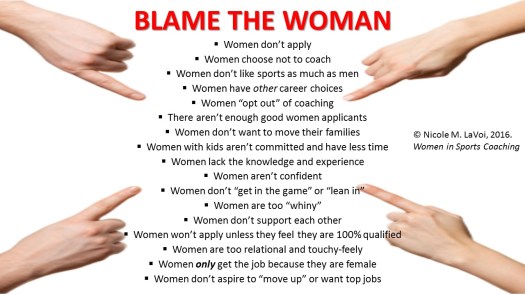

In Part I of this series I outlined why the way women sport  coaches are framed is often problematic. For example there are many popular narratives about why the percentage of women coaches remains stagnant, and many of them blame women. When women are blamed, the system AROUND the women does not have to change.

coaches are framed is often problematic. For example there are many popular narratives about why the percentage of women coaches remains stagnant, and many of them blame women. When women are blamed, the system AROUND the women does not have to change.

Below is a list of common “blame the women” narratives I have compiled over the last 10+ years in doing research, advocacy and education for women sport coaches. Through my research I, and others, collect data that dispels or supports these narratives. Based on existing data, I can tell you very little data exists to support these narratives (although there is a LOT of anecdotal evidence and individual opinions, but that doesn’t mean the narrative(s) is true).

If you know of data the helps dispel or support any of these narratives, please let me know! (nmlavoi@gmail.com). In my next blogs I will provide counter narratives to this list above. #SHECANCOACH